AGENCY

washington, Mar 27

President Bill Clinton’s visit to India from March 20 to 25, 2000, was a remarkable journey that set the stage for the US-India partnership that has developed so fruitfully over the ensuing 25 years. The trip was particularly noteworthy coming less than two years after bilateral relations hit their nadir in May 1998 when India and then Pakistan tested nuclear weapons.

From sanctions to “natural allies”

The US (and Western) response to the nuclear tests was sanctions, followed by more sanctions. But President Clinton realised that the sanctions approach was unrealistic and unproductive. He told Deputy Secretary of State Strobe Talbott a month after the tests that he wanted India to be “front and centre for the rest of his presidency.”

Talbott and his Indian counterpart Jaswant Singh began an intense and ultimately productive dialogue that led to the visit. Pakistan played a role too. When the Pakistani military crossed the Line of Control at Kargil in the winter of 1999, Pakistan’s Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif sought Clinton’s intervention. To Sharif’s dismay, Clinton instead pushed Sharif to pull back his troops to the Pakistani side, demonstrating to often-skeptical Indian leaders that US involvement in the subcontinent could be fair-minded and even redound to Delhi’s benefit.

The visit

When Clinton came to Delhi—22 years after the last such visit by US President Jimmy Carter—he made a point of expressing respect for India and its place in the world. He was the first American leader to treat India as a partner in world affairs rather than as a problem case to be dealt with by the big powers. He was not playing the China card or trying to resolve Kashmir. He was treating India as a serious player whose opinions mattered on the global stage. And thanks especially to Clinton’s help on Kargil, he was knocking on an open door in Delhi.

Clinton’s superb communications skills were put to good use on the trip, especially in his address to a joint session of Parliament in which he demonstrated the respect India expected for its history and democracy without shying away from discussing our differences over nuclear proliferation.

In the speech, he expressed gratitude for the life and work of Mahatma Gandhi “without which the civil rights revolution in the US could not have succeeded peacefully.” He praised India’s democracy and commiserated over the terrorism it faced, saying “borders cannot be redrawn in blood,” a reference to the killing of 36 Sikhs in Kashmir two days before his speech.

He said that only India could decide its course on the continued development of nuclear weapons but called for continued discussion and warned of the dangers the US had experienced in the Cold War. He asked, above all, for dialogue and partnership between our countries.

External Affairs Minister Jaswant Singh said the parliamentary speech received “a response from my hard-headed political compatriots that I have never seen accorded a visiting head of state.” Journalists compared his welcome to that given to a rock star. The Indian government published the speech and Clinton’s other remarks in a commemorative booklet.

Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee called Clinton’s visit a “transformation in our relations” and described the two countries as “natural allies”.

In a prescient Vision Statement, the two leaders talked about the promise of globalisation as well as the threat of terrorism. They proclaimed their nations “partners in peace, committed to strengthening the international security system, including the United Nations.” They committed to regular meetings at the head of government level, and Vajpayee travelled to Washington in September that year.

The White House wanted trade and investment to be a high point of the trip. Commerce Secretary William Daley was on the delegation and oversaw the establishment of a dialogue on trade and commerce and a working group on multilateral trade issues. A Science and Technology Forum was created.

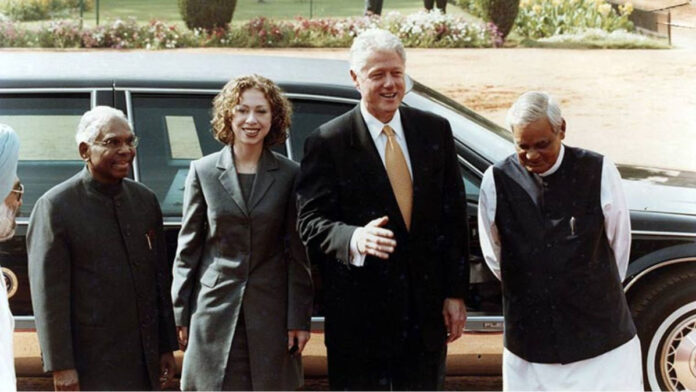

Unlike previous POTUS visitors, Clinton chose to visit India outside the Delhi/Agra axis. He, his daughter and his mother-in-law travelled to Jaipur, including visits to a village and to a tiger reserve. There was business to be done in Agra (environmental cooperation) and in Hyderabad (highlighting USAID cooperation in combating TB, malaria and HIV/AIDS, and acknowledging India’s accomplishments in information technology). He concluded his visit in Mumbai where he met a panel of India’s youth, visited the stock exchange, and attended a reception with business leaders.

Finally, while the “five days versus five hours” contrast between the trips to India and Pakistan was predicated more on security concerns than any intent to denigrate Pakistan, the Clinton visit in 2000 was the beginning of the end of US efforts to try to balance its relations with India and Pakistan.

The aftermath

Clinton never did lift the nuclear sanctions. That was left to his successor George W. Bush who also took the huge step of acknowledging India’s nuclear program and restarting civil nuclear cooperation after India took steps to separate its civil and nuclear program. With that India-specific agreement, the hyphen in India-Pakistan was cancelled forever. It’s hard to conceive of this 2005 agreement without the good will and confidence on both sides engendered by the Clinton-Vajpayee relationship five years earlier.

The dialogue at the United Nations continued to grow and ten years later, Barack Obama took it to the next level, describing India as a natural addition to the permanent membership of the Security Council, a commitment that has been reiterated by all three of his successors.

Now, Presidential and Prime Ministerial visits have become routine. PM Narendra Modi was one of President Trump’s first visitors this year and Trump has committed to go to Delhi later in 2025.

US and Indian scientists have collaborated for 25 years to end infectious diseases like TB and HIV/AIDS, even as President Trump’s suspension of USAID and CDC projects in January 2025 has created uncertainty over medical cooperation.

Nobody in 2000 would have envisioned the Quad, a cooperative agreement focused increasingly on security, and links India with the US, Japan, and Australia. The “natural allies” Vajpayee talked about have hewed closer to defence ties than he was probably contemplating. Joint military exercises are routine and defence cooperation and co-production are prospering. Lockheed and Boeing are more likely to sign big defence deals with Delhi than the state-owned Russian companies on which the Indian military used to depend. From F-14 engines to F-35 jets, India is being offered ever-more sophisticated technology in US efforts to wean it away from traditional dependence on Russia.

US policymakers are too often preoccupied with crises in Ukraine, the Middle East, and the Korean Peninsula. So, US-India relations are not always, as Clinton hoped, at the forefront of US diplomacy. But when Washington and Delhi look at what our two countries have accomplished together over 25 years, they have every reason to be proud of where we are today.